The Hawaiian Monk Seal Hospital – Kona’s Ke Kai Ola

After my freshman year of high school, I spent the summer volunteering for a remarkable hospital in Sausalito, California – The Marine Mammal Center. I separated frozen fishes, washed dishes, and hosed down pens – all the while memorizing the shapes, smells, and sounds of Pacific harbor seals, Northern elephant seal pups, and California sea lions. Curiosity about marine life has always been a driver of my life, so I made sure to take in as much science as I could.

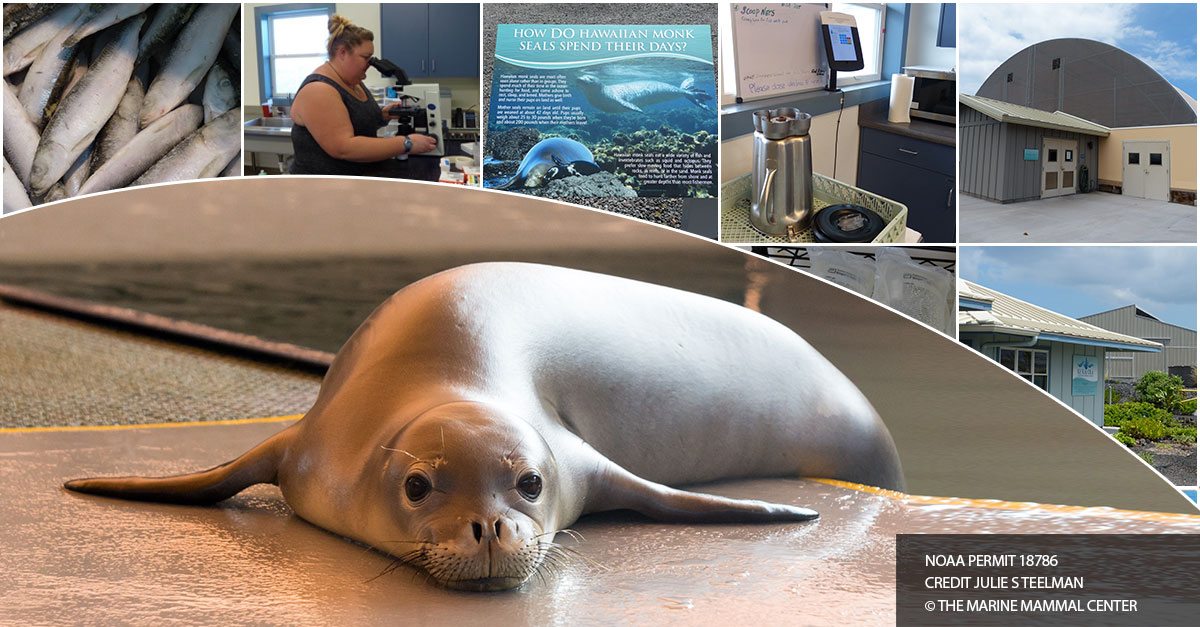

Twenty years later, in 2014, exciting news came down the pipe. The Marine Mammal Center had just built another facility, in Kona! The endangered Hawaiian monk seal now had one of the best advocates possible in their corner – dedicated experts in pinniped rescue, rehabilitation, and release. (Do you remember that last phrase from the 2016 Disney film “Finding Dory?” Rescue, rehabilitation, and release has been The Marine Mammal Center’s motto since 1975. Groovy, right? Totally!)

The new hospital was named Ke Kai Ola, which translates from Hawaiian to “The Healing Sea.” When construction was complete, Ke Kai Ola received a blessing in the Native Hawaiian tradition, and the facility joyfully opened its pools!

The endangered Hawaiian monk seal is endemic to the Hawaiian Island chain, and it is the only seal that lives in these islands. Ilio-holo-i-ka-uaua, the species’ Hawaiian name, means “dog that runs in rough water.” These intelligent mammals spend most of their time alone, at sea, though females have been seen caring for the pups of other mothers. When they aren’t out hunting, traveling, or resting underwater, monk seals enjoy taking long walks on the beach. Well, perhaps not too long (have you seen a seal move on land?), but about one third of their lives are spent resting on sand somewhere.

The bulk of the species lives in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands: a federally protected chain of islands, atolls, and reefs that extends over 1200 miles (2000 kilometers) beyond Kauai. (You may have heard of Midway Island? Excellent! Midway is part of that chain.) A smaller number of seals spend their time in the main Hawaiian Islands, which is the paradise we’re thinking of when we shout to our co-workers, “Yeah, baby, I’m going to Hawaii next week!”

The Hawaiian monk seal population is now estimated to be 1400 strong, and they are protected under both the U.S. Endangered Species Act and the U.S. Marine Mammal Protection Act. The Caribbean monk seal was lost to us in 2008, and at the time of this writing (March 2017), less than 600 Mediterranean monk seals are out there plying the seas. (To put things in perspective, you could easily have that many friends on Facebook.)

Hawaiian monk seals striving to survive face rough seas on a daily basis. Each must contend with toxins, parasites, disease, sharks, entanglement, and pollution. Then there’s lack of prey, sea level rise, poor pup survival, and the sometime aggression of male seals toward pups.

Now, you can see why the Hawaiian monk seal could use a hand (or a flipper, depending on your perspective). It’s a good thing The Marine Mammal Center came to the rescue! Ke Kai Ola is the first permanent care facility devoted to the rehabilitation of this species.

Most Hawaiian monk seals do not need hands-on care, but all of them are protected by law. That’s where Ke Kai Ola’s response team comes in!

The response team keeps an eye on Big Island monk seals that are living in the wild. Remember, these endangered predators spend about one third of their time hauled out on land, so it’s only natural that their taste in beaches sometimes overlaps with ours. Response team members teach beachgoers how to share the sand safely with seals.

These Ke Kai Ola volunteers take time to talk about Hawaiian monk seal natural history, the reasons behind the safe and lawful distance requirement (at least 100 feet/30 meters when beach size allows it), and what number to call when a seal is sighted. The Ke Kai Ola hotline takes calls 24 hours a day at (808)987-0765. (If you add that number to your Favorites list, everyone will think you’re totally cool!)

When I arrived at the hospital on a still summer morning, I was greeted by Deb Wickham – the Operations Manager, and two Marine Mammal Center volunteers – Claire Trester and Aubrey St. Marie. Marjorie Erway joined us later, when her afternoon shift began. Everyone gave me a very warm welcome, which honestly wasn’t too hard to do, because it is really, really hot in Kona!

I had learned ahead of time that I would be able to tour the hospital grounds, watch the seals through real-time surveillance cameras, and utilize photos taken by Ke Kai Ola’s volunteer photographer, Julie Steelman. Anyone working near the seals takes great pains to minimize unnecessary human contact, even when it comes to talking out loud. It’s important not to teach seals that people offer free meals. (At the very least, they need to understand we’re going dutch.) After all, the reason for recovery is to make seals stronger so they can forage on their own. As Deb put it, “The more you do for them, the less they have to do.” And she’s so right!

Deb Wickham became a registered veterinary technician in 1984, and she has been an integral part of The Marine Mammal Center since 1992. (In fact, she remembered training me on the coast of California in 1994!) When it was time for the new hospital to open in Kona, Deb moved to the middle of the ocean to help. She is a quietly competent leader, volunteer teacher, husbandry manager, and central life support of The Marine Mammal Center: Kona edition.

“Saving a species takes a village,” Deb said to me, nodding. “The credit goes to the volunteers. I give the tools.”

At 7:30 every morning, volunteers are in house weighing fish thawed overnight, disinfecting feeding tubes, and mixing up the tastiest, healthiest, and smelliest herring shakes you can imagine! Some patients are old enough and strong enough to eat whole fish, while others have to be tube-fed for a time. When whole fishes are used, an individually-tailored cocktail of vitamins, minerals, and medications are slid beneath their gills. Each fish is offered head-first to the corresponding seal.

As patients become stronger and healthier, their meals are often delivered in a box. (No, not an ono bento box!) When seals hunt in real life, they often need to move things around to find and catch octopuses, squid, crustaceans, eels, and fishes. Ke Kai Ola’s fish box is an enrichment tool to spark these foraging behaviors. Rocks and sand are placed on top of the closed plastic container, which hides one or more delicious fishes.

Technically, Ke Kai Ola can house up to ten seals at a time, but eight has seemed to be a nice, comfortable number so far. Eight may seem like a small amount, but just two years after opening, the facility had already seen over 1% of the entire species!

Each pool is quarantined from the others, and runs on ocean water piped in straight from the coast. The water flows in and out, but any medicines used are filtered out and captured before they leave the building. This dynamic keeps the monk seals that are inside – and the ocean that is outside – as healthy as possible. Because feral cats and mongoose could find this place wonderful too (Who wants fish?), the builders secured the pool room against any small animal entry.

Between feedings, the hospital to-do list includes washing dishes, cleaning, readying fish, and hosing poop off the floors, among other things. “Very glamorous work,” Deb described, chuckling. Constant maintenance is necessary for the entire facility, including the office, kitchen, treatment room, pens, pools, and education courtyard.

Marjorie, the hospital’s administrative assistant, keeps all the paperwork sorted out. About seven years ago, she toured the Sausalito center and was “blown away by the number of volunteers compared to paid staff.” Through her financially analytical eyes, this ratio demonstrated that the nonprofit was worth supporting: the facility was clearly good with their money.

Now that Marjorie has a role in the Kona center, her favorite part about it is “just being here.”

I understand her feeling. While I explored quietly, taking photos and video, I became most excited when I heard my very first monk seal sound. It was a long braaaap, like a belch. I don’t know what it meant to the seals, but I will remember it for always.

Ke Kai Ola’s treatment room is furnished with a tall stainless steel table, an anesthesia machine, IV bags, and a portable ultrasound at the ready. (Considering all the marine debris floating around, you never know what a seal may have swallowed.) To check the seals’ CBCs, the medical team draws blood and sends the samples to a lab on the island. They also do fecal flotations to look for parasites. (I didn’t ask how those worked, so you can let that breath out.)

Seals are weighed on a weekly basis. One of Ke Kai Ola’s cool catch phrases is “Fatter is Better,” and every week offers a chance to seal-abrate!

A female seal named Meleana came to the center from Kure Atoll – the farthest Northwestern Hawaiian Island still breaking the surface. When she was brought in at five months old, her weight was only 18 kilograms (40 pounds) – the same as a pup’s weight at birth, and she could barely raise her head. When she was released at Kure six months later, Meleana was a healthy, active 109 kilograms (240 pounds)!

Malnutrition is one of the most common situations treated, but sometimes a more unique case presents itself. On one occasion, a seal from Lisianski Island arrived with a two-foot-long eel up his nose! Luckily, Michelle Barbieri – a NOAA Wildlife Veterinary Medical Officer, and one of Ke Kai Ola’s veterinarians – was perfectly prepared to handle the slippery situation.

The space is “not really for surgery,” Deb explained, but if necessary, they “could do it here in a pinch.” One thing about The Marine Mammal Center facilities, and the people who keep them succeeding, is that every one of them is resourceful as an octopus.

Patients are deemed ready for release when they are as fat as possible, healthy, and able to forage on their own. Once this determination has been made, the “to-go” seals are outfitted with a three-month satellite tag, and herded into a crate with plenty of airflow; every side is made of large chain link. After the seals are all packed, they are kindly delivered to their respective home atolls by one of NOAA’s ships. Talk about door-to-door service! Update: In the summer of 2017, the four monk seals in the photographs and video in this article were returned – fat, active, and healthy – to their Northwestern Hawaiian Islands!

As you can see, Ke Kai Ola is not an island unto itself. The nongovernmental body works within a plethora of partnerships, including the one they’re cultivating with the local fishing community.

The Marine Mammal Center recommends fishing with barbless circle hooks, which retain the ability to catch epic fish, but are safer for other animals. If seals or turtles are unintentionally hooked, they can expel this type more easily. (FYI, a crimper can be used to squeeze down the barbs of regular hooks to save money and endangered species. It’s a win/win!) And if you believe that monk seals are competing with nearshore fishermen for catch, know that – altogether – all 200 seals that live around the main Hawaiian Islands eat just one pound of fish per square mile per day.*

Ke Kai Ola maintains magnificent relationships with the U.S. Coast Guard, National Marine Fisheries Service of NOAA, Natural Energy Laboratory Hawaii Authority, Hawaii Wildlife Fund, Department of Land and Natural Resources, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the Kohala Center, Dolphin Quest, the Disney Conservation Fund, and Four Seasons Resort Hualalai. (I’d like to thank the Academy, and braaaap. . . .)

Ke Kai Ola, NOAA, and organizations like Malama Monk Seal are increasing marine mammal education and awareness just beautifully! When it comes to the hospital’s tremendous goal of bringing these seals back from the brink of extinction, Deb had this to say:

“Do I think we’re going to do it? Yes. I’ve met so many dedicated volunteers, with so much energy pushing towards survival. I am thankful and honored to be here to help save a species.”

Ke Kai Ola would love more volunteers on the Big Island – both in the care department, and also to help maintain the pens and pools.

To donate to the facility, take a tour, and/or volunteer, you can see the center’s website or contact Deb directly at wickhamd@tmmc.org.

* “NOAA Technical Memo – Estimation of Hawaiian monk seal consumption in relation to ecosystem biomass and overlap with fisheries in the main Hawaiian Islands”